Increased vulnerability to hunger and malnutrition in tribal communities of Jharkhand due to COVID19 pandemic

Despite the state government launching several initiatives, such as Mukhya Mantri Didi Kitchen, helplines for migrant workers and a 100-day job guarantee scheme for urban unskilled workers, Jharkhand needs to do a lot more to improve its performance on nutrition that has taken a hit in the pandemic.

Jharkhand has one of the highest levels of undernutrition in the country. Photo: Unicef India

Neha Saigal and Saumya Shrivastava

The COVID19 pandemic has hit rural and tribal communities across India and Jharkhand is no exception. The state has always been plagued with high hunger and malnutrition which has worsened due to the pandemic. With support of the Social Audit Unit (SAU) of the Government of Jharkhand, the Jharkhand State Food Commission has initiated social audits to understand the accessibility to government’s food security and nutrition schemes during the ongoing pandemic.

Through our research and extensive discussions with the stakeholders, we tried to understand the prevalence of hunger and malnutrition post the COVID-19 pandemic, and also analysed the progress made in Jharkhand on food security and nutrition over the last fifteen years and the impact of the COVID on this progress.

We found that despite the state government launching several initiatives, such as Mukhya Mantri Didi Kitchen, helplines for migrant workers and a 100-day job guarantee scheme for urban unskilled workers, Jharkhand has a lot more work to do to improve its performance on nutrition.

This was also highlighted by Gurjeet Singh, State Co-ordinator of the Social Audit Unit (SAU), who said: “Hunger and malnutrition has always been a problem in Jharkhand, especially during periods when the stocks are depleted, like the monsoons. Many factors have played a role, the increase in urbanisation, limited irrigation and disappearing traditional food varieties.”

Also Read: For anganwadis, Corona shutdown could mean safety from disease, not from hunger

Pre-COVID19 scenario

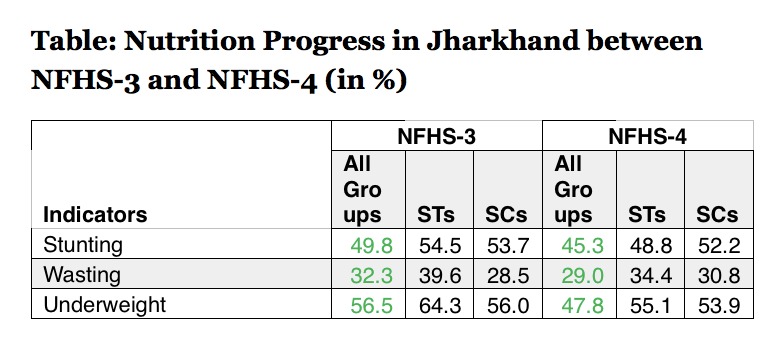

Jharkhand has one of the highest levels of undernutrition in the country as per the National Family Health Survey-4 (NFHS-4), and much higher than the national average. As of 2015-16, 45.3 per cent children under-5 years of age were stunted, 29 per cent wasted and 46.8 per cent underweight, compared to 49.8 per cent stunted, 32.3 per cent wasted and 56.5 per cent underweight children in 2005-06 as per the NFHS-3.

Moreover, levels of undernutrition among the Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Scheduled Castes (SCs) in the state are also higher than the overall state averages — 48.8 per cent STs and 52.2 per cent SCs were stunted in 2015-16.

Jharkhand has seen improvements in several food security and nutrition determinants in the period between the NFHS-3 and NFHS-4. Notably, the proportion of women with below normal body mass index (BMI), an important determinant of child nutrition, has improved by 11.5 percentage points from 42.9 per cent in 2005-06 (NFHS-3) to 31.5 per cent in 2015-16 (NFHS-4).

Similarly, there have been improvements in women’s age of marriage and childbearing; 11.9 per cent women in age group 15-19 years were mothers at time of survey in 2015-16 (NFHS-4), compared to 27.5 per cent in 2005-06 (NFHS-3).

Also Read: What is the cost of childhood wasting and severe acute malnutrition in India?

Improvements in maternal and child health

Access to maternal healthcare has also improved in Jharkhand; the proportion of women who received ante-natal check-up from a skilled provider increased from 52.7 per cent during NFHS-3 to 69.7 per cent during NFHS-4. Similarly, women who received post-natal check-ups increased from 19.6 per cent to 52.8 per cent, from NFHS-3 to NFHS-4, respectively.

The coverage of anganwadi centre (AWC) services has also improved during this period. Between NFHS-3 and NFHS-4, the proportion who received supplementary nutrition among children aged 0-71 months increased from 36.5 per cent to 50.8 per cent, pregnant women increased from 34.7 per cent to 68.4 per cent and lactating women increased from 35.9 per cent to 63.6 per cent, respectively.

Data also shows that across different food categories considered healthy (such as milk or curd, green leafy vegetables, meat, fish, eggs, pulses, or beans), weekly consumption has improved between NFHS-3 and NFHS-4 for both women and men but still remains low.

No doubt that Jharkhand has made progress between the two NFHS surveys but it continues to do worse than the national average in almost all determinants.

As Jharkhand did not feature in the first round of NFHS-5 findings, it is challenging to assess the prevalence of hunger and malnutrition in the state, but findings from surveys conducted during the lockdown signify a risky trend, in contrast to the progress over the last decade or so.

Also Read: Women ‘Poshan Champions’ tackle malnutrition while puncturing patriarchy

Post-COVID scenario

The Hunger Watch report surveyed 11 states, including Jharkhand, between September and October last year, to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown. The report presents a grim situation of the status of hunger and nutrition especially among India’s most economic and socially vulnerable groups, Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims and women, observing that this was a result of increased unemployment and decreased incomes.

Jharkhand is exceptionally vulnerable because of its high tribal population (close to 26 per cent) including nine Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs). According to the Hunger Watch report, PVTGs and the Dalits were worst impacted in consumption of nutritious food, compared to other social groups.

Another survey, the Rapid Rural Community Response to Covid19, Household survey, conducted between December 2020 and January 2021, showed Jharkhand performed the worst on factors determining food security and nutrition. According to the survey, the number of people earning below Rs 5,000 increased by 12 percentage points post COVID19 in Jharkhand and over 53 per cent respondents reported job loss during the pandemic — highest among 11 states.

Also Read: 80% rural respondents said their work was affected due to the lockdown

The state had the highest number of seasonal migrants, and migrants who returned to the state, most of whom were STs. Considering the lockdown caused a massive exodus of migrants, migration is an important factor for food security and hunger. Jharkhand also performed the worst in food consumption with 68 per cent respondents cutting down on food, with protein intake impacted the most.

The Jharkhand government itself conducted concurrent social audits, initiated by the State Food Commission and Social Audit Unit, covering 23 districts during April-May 2020. The audit showed that over 40 per cent families availing ration for two months from the government did not receive the entitled quantity during the lockdown.

Under the Mid-Day Meal (MDM) scheme, 20 per cent families did not receive ration during the lockdown, and 40 per cent families reported that the quality and quantity of food grains received was not appropriate.

Under the anganwadi centre (AWC) services, 11 per cent families were not registered to access the benefits. Of those registered, 34 per cent families did not receive nutrition supplements from the AWCs and among those who received nutrition, 20 per cent did not receive the stipulated quantity.

“The ICDS is the worst affected by the COVID19 pandemic. It hasn’t been operational since February 2020, due to lack of policy direction on whether Take Home Rations should be packaged or supplied through local Self Help Groups and operate on a reimbursement model which is inconvenient for anganwadi workers,” stated Gurjeet Singh, State Co-ordinator of the Social Audit Unit.

Increased vulnerability to hunger and malnutrition post COVID

Jharkhand is primarily a rural state, rich in natural resources but considered one of the poorer states in India, fiscally. Prior to COVID19, the state was already experiencing an increase in unemployment and further witnessed highest job losses and decrease in incomes during the pandemic, adversely impacting food consumption.

During this time, MGNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005) played a crucial role in providing employment to a large proportion of the population, noted Singh, adding that “the state should have focused on increasing the number of workdays under MNREGA.”

Also Read: Rising concern: Rural India faces the double burden of undernutrition and obesity

Surveys done during the lockdown indicate that marginalised social groups have been the most impacted by the pandemic, especially the SCs, STs and PVTGs. Jharkhand has a diverse population, with around 40 per cent belonging to either SCs (12.1 per cent) or STs (26.2 per cent) as per the Census 2011 and several groups of PVTGs who are considered developmentally the worst-off among all social groups.

Jharkhand also had the highest proportion of migrant workers returning to the state during the lockdown in 2020. While multiple factors influence malnutrition, access to employment and livelihood is critical in determining household food security. The limited data on nutrition determinants makes it difficult to understand the status of under-nutrition in Jharkhand, but given the impact on access to AWC services, and the reduction of food consumption, under-nutrition has potentially worsened post the lockdown.

Initiatives by the Jharkhand government

To address the challenging situation around hunger and malnutrition, the Government of Jharkhand set up Mukhya Mantri Didi Kitchen (MMDK), community kitchens run by women self-help groups, providing food during the lockdown to the most deprived households. While this model was helpful, the meal frequency was reduced to one meal from two meals a day after a few months during the lockdown.

Also Read: In the absence of mid-day meals, children in Bihar survive on roti-onion, bhaat-achar

During the first wave of COVID-19, Jharkhand took several initiatives to support its most vulnerable. “Jharkhand launched migrant helplines, panchayats received funds from the Finance Commission to set-up isolation centres and arrange food and sanitation. The state also launched a 100-day job guarantee scheme for urban unskilled workers and schemes to revive the rural economy especially for landless labourers” mentioned Singh.

Singh informed that Jharkhand was now preparing for the third wave, but nutrition had taken a backseat. The state needs to urgently introduce eggs in AWCs as a reduction in protein-intake during the pandemic has been observed.

The road ahead

Jharkhand needs to quickly adopt recommendations by experts and prioritise action towards ensuring food security and nutrition. The state should universalise public distribution system and provide every individual 10kg of grains, 1.5kg pulses, and 800gm cooking oil each month for at least the next six months; distribute nutritious hot cooked meals (including eggs) through anganwadi centres and MDM; revive all ICDS services; enhanced social security pensions of at least Rs 2,000 for elderly, widows, and disabled persons.

It should also ensure maternity entitlements under Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana without conditionalities; strengthen food subsidy and provide support to farmers through the minimum support price (MSP) of crops; increase number of workdays under MGNREGA to 200 days a year and ensure timely payments (linked to minimum wages) and continue implementation of urban employment guarantee scheme to help urban poor hit by the pandemic.

Saigal is a social development consultant based in Bengaluru, and her work focuses on intersectionality of gender, health and nutrition equity. Shrivastava is a development consultant with IPE Global based in New Delhi, and her work focuses on improving nutrition equity and accountability. Views are personal.

Also Read: ‘Rice and wheat in India are lot less nutritious than they were 50 years ago’