The criminality of fly ash management

On April 10, the dyke of a fly ash pond of Sasan Ultra Mega Power Project in Singrauli collapsed. Such incidents are the consequence of what the data on fly ash utilisation has been showing all along. The management of fly ash, which is the by-product of burning coal to produce energy, has been a regulatory failure

Manju Menon, Debayan Gupta and Kanchi Kohli

On April, 10 2020, the dyke of a fly ash pond of Sasan Ultra Mega Power Project in Singrauli, Madhya Pradesh collapsed. The slurry collected in the pond made its way into agricultural fields and swept away six people, of whom at least two people are reported to be dead. This is the third incident of a fly ash pond breach in Singrauli in a span of less than one year.

In August 2019, Essar Mahan Power Plant’s ash pond for its 1,200 MegaWatt (MW) Power Plant had “leaked”. It destroyed almost 500 acres of farmland and the slurry trapped five children, who were eventually rescued by the District Administration. This was followed by a breach in the ash pond of Vindhyachal Thermal Power Plant run by the NTPC which damaged 30 acres of land and swept away 15 cows in October 2019.

Such “accidents” have also been reported in other coal power hubs in the country. In Korba, Chhattisgarh, Bharat Aluminium Company’s (BALCO) ash pond for its 1,200 MW power project crumbled in 2017 leading to several thousands of tonnes of fly ash slurry making its way into the Belgiri river channel which flows near the ash pond. These incidents are the consequence of what the data on fly ash utilisation has been showing all along. The management of fly ash, which is the by-product of burning coal to produce energy, has been a regulatory failure.

The regulatory myth about Fly Ash Utilisation

In a December 2017 report of the Central Electricity Authority, RK Verma, the then chairperson states that fly ash was an “hazardous industrial waste”. Yet coal power was seen as a necessary public good and fly ash production, its inevitable cost. Technological research on its use by various scientific bodies gave fly ash “the status of useful and saleable commodity”. In 1999, the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) issued a Fly Ash (Utilisation) Notification under the Environment (Protection) Act, with a two-fold purpose: firstly, to prevent the dumping and disposal of fly ash on land and secondly, to conserve top-soil by restricting its use in brick making. The Notification required all Thermal Power Plants (TPP) to ensure the use of fly ash in brick making, road construction, cement manufacturing and agriculture within a 50 km radius of the TPP. The Notification envisioned a 100% utilisation of fly ash within nine years from the issue of the Notification. However, the Notification did not specify any repercussions if the utilisation was not achieved by TPPs. A 2003 amendment to the Notification increased the radius of fly ash utilisation from 50 km to 100 km in the interest of achieving the target.

In 2007, most TPPs were far from achieving utilisation targets. In an act of regulatory negligence that exposed many lives to pollution from stored fly ash, more amendments were made in 2009 to extend the deadlines for compliance by operational TPPs to five years and by newly-commissioned TPPs to four years. The TPPs failed to comply with this deadline too. Another amendment in 2016 further pushed the deadline to December 31, 2017 and also increased the radius for utilisation from 100 km to 300 km. A draft notification was issued in February 2019. While this draft did not extend the deadline or the radius, it provided for banning red brick kilns and set up the minimum weight percentage of fly ash to be used in the various avenues of utilisation within the 300 km radius of a TPP. A new action plan of the government has extended the time for compliance to 2021.

The non-implementation of the above norms and the resultant pollution from fly ash mismanagement has been subject to litigation in courts and tribunals. These court decisions led to the setting up of specific committees in certain regions, such as Singrauli. Action Plans were prepared to specifically deal with fly ash utilisation, such as the Raipur Declaration of 2017 adopted by the Chhattisgarh government. The NGT charged power producers who had failed to achieve 100% utilisation by December 2017 with fines of “up to Rs 5 crore” based on their capacity. In 2018, the Niti Ayog set up a committee to incentivise fly ash utilisation by TPPs. They also created a mobile app to track fly ash utilisation compliance by TPPs.

The regulatory compliance of fly ash utilisation has remained unachievable despite these high-level government and court interventions. As per the data available with the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) for 2018-19, of the 195 TPPs, only 103 had managed to achieve their phased out targets of fly ash utilisation and 83 had failed to do so. It must be remembered that official data on the efficiency of environmental management measures such as fly ash use is likely to be only an indicator of a problem of much a greater scale.

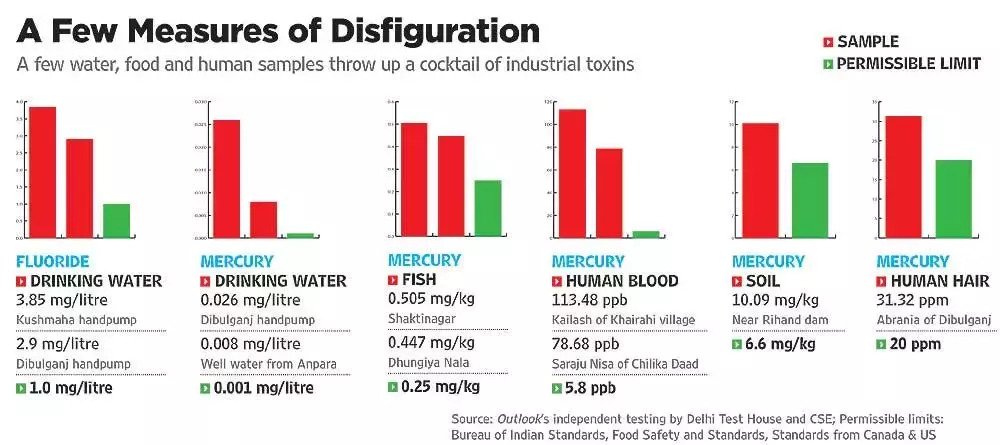

These institutions are now complicit in perpetuating a regulatory myth and exposing large human and animal populations in India’s “coal belt” to high levels of harmful heavy metals in their air and water, the basis of all survival.

A case for criminality

There has been an increase in the number of coal-fired power plants and the production of toxic fly ash over the years. From a mere 68.88 million tonnes (MT) in the years 1996-1997, fly ash production increased almost three-fold by 2018-2019 and stands at 217.04 MT. Of the 217.04 MT, 168.40, i.e 77% of the fly ash was utilised according to official data. This means that at least 48.64 MT of fly ash is lying unutilised. Fly ash is also not used as and when produced. It has to necessarily be stored in huge ash reservoirs called “ponds” until some use is created for it. There are also several cases of recorded “indiscriminate dumping” of fly ash on agricultural farms, water streams and forest areas and many more that may be unrecorded by district authorities despite complaints from local people. These result in crop damages, loss of land productivity and abandonment of farms polluted by dried ash that blows from the ponds or by irrigation water that is laced with toxic slurry.

Transportation of fly ash also increases the number of people exposed to it. In all, communities living in coal power producing regions face acute water and air pollution as an everyday fact of life making them vulnerable to other illness and diseases. Studies by State Health Resource Centre and NIE warn that such populations are also more likely to suffer from COVID 19. These communities also put in the way of sudden life-threatening ash pond breaches like the ones at Singrauli.

On November 8, 2018, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) issued directions to all State Pollution Control Boards (SPCB) to formulate steps for utilising fly ash and file reports before the CPCB. Several RTI applications filed by us since January 2019 revealed that only six states — Sikkim, Tripura, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Mizoram and Nagaland — had submitted responses. When the CPCB was asked if any action would be taken against the states who have failed to submit compliance reports, the CPCB replied in the negative.

Sikkim, Tripura, Mizoram and Nagaland PCBs stated that the directions do not apply to them as there are no operational power plants in the state. Chhattisgarh PCB replied that the fly ash would be used to construct over 2,000 kms of railway lines proposed in various parts of the State. Madhya Pradesh PCB’s point-wise reply show the true constraints in fly ash management. It states that only a small amount of fly ash generated can be used in brick making and civil construction. The only users who can utilise fly ash in large quantities are coal mines, but the mine operators refuse to cooperate. The reply also stated that the railways, which undertake large construction projects, do not use fly ash in their construction works.

The reliance on coal for electricity generation is treated as a necessity, but its performance is rarely assessed against these massive environmental, economic and public health costs. Enviro-legal instruments such as the fly ash utilisation notification are not held accountable for the impacts that they have sanctioned. The Notification’s amendments have expanded the zone and time exposure of fly ash pollution in coal power production regions. The myth of effective utilisation of fly ash has been in place for 20 years and it is maintained by many technical bodies and institutions. All of them together have failed to realise the full utilisation of fly ash, contain indiscriminate dumping and prevent these killer ash pond breaches. The Fly Ash (Utilisation) Notification is a good example of how environmental managerialism works in favour of projects and against communities.

(The authors are environmental researchers at the Centre for Policy Research)