Women facing livelihood crisis in a fishing belt in Andhra spark a change; set up small businesses

The fisheries sector provides employment to more than 14 million people. However, these fisherfolk are staring at a gloomy future as livelihoods get affected and unemployment looms

Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh

Anjali Devi’s family once faced hardship because her husband, a creek-based fisherman, struggled to catch enough fish. Today, she supports her family.

Anjali is now part of a women’s self-help group in the tiny hamlet of Kobbarichettu peta — in the Tallarevu mandal of Andhra Pradesh’s East Godavari district — that is engaged in the business of vending dry fish. She, along with other women of the group, has set up the business with the help of a loan they received from the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation. This has put an end to her suffering.

“I have a son who is now a CRPF (Central Reserve Police Force) personnel posted in Jammu and Kashmir and my daughter is in her fourth year of engineering studies. My husband has left fishing and drives an auto-rickshaw,” said Anjali, talking about the impact of her new business.

P Madula, a mother of two daughters, is also a member of the group. She runs a tailoring shop. “Our families were involved in fishing, but since the catch started decreasing, we were left with nothing. After I became a part of this self-help group, I learned to manage my resources better,” she said.

This is the story of many families that have for long been dependent on fishing — the women are now taking up new occupations to support the fishermen hit by dwindling catch.

Reduced fish catch

With a coastline of over 7,500 km, India is the third-largest fish producer in the world. The fisheries sector supports more than four million fisherfolk and provides employment to more than 14 million people.

The total fish production in India during 2017-18 was 12.6 million metric tonnes and the export was worth Rs 45,106.89 crore, as per the National Fisheries Development Board, an autonomous organisation under the Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Animal Husbandry, Dairying and Fisheries, Government of India.

While the number presents a pretty picture, those responsible for it, however, stare at a gloomy future as livelihoods get affected and unemployment looms, especially in the coastal belts of Andhra Pradesh. At issue is the future of fisherfolk like Gangadhar Prasad, a fisherman, and P Dharma Rao, the owner a mechanised fishing boat, who are witnessing a change that is threatening their only source of income.

Dharma, 38, and Prasad, 35, work at the fishing harbour of Kakinada, the headquarters of the East Godavari district with a fisher population of more than 3.8 lakh, of which over 75,000 are active, as per the state fisheries department.

“We are experiencing reduced catch as a result of pollution from the nearby industries. We were able to catch fish at a depth of 80 metres below the sea surface, but now we have to go deeper,” said Dharma. His father is a fisherman, but his brother chose to stay away from the family occupation and instead went for education.

“Usually, our fishing trips last for 6-12 days in the sea. On good days, we catch some 2,000 kg of fish,” said Prasad.

“At least Rs 3-4 lakh is required for each voyage to pay the crew’s wages, for fuel for the boat, and for ice to store the catch. The profit ranges from sometimes zero to sometimes Rs 1-2 lakh and is shared among the workers. I have to pay for the repair and maintenance of the boat also from any profit,” said Dharma. “Also, with cyclones and storms, the risk in fishing is now more than ever.”

The locals believe that marine pollution caused by nearby Kakinada Seaports Limited (KSPL) and fertiliser and edible oil refineries is killing fish and destroying their eggs, thus reducing the catch. Their protests have fallen on deaf ears. In 10 years till 2015, the KSPL had expanded its port length from 610 metres to 2,500 metres and continues to do so, it was reported.

“The marine fish catch has come down over the years, which may be due to overexploitation,” said Dr R Ramasubramanian, principal scientist in coastal systems research programme, MS Swaminathan Research Foundation.

According to him, the reduction can be caused by many factors. “It depends on the seasons. The fish catch, particularly the shrimp catch after the floods, has increased, but that of tuna has come down. One of the reasons for less catch is the lack of freshwater supply as dams have been constructed on the Krishna river. For a good catch, freshwater is required as it brings a lot of nutrients. Cyclones, which also account for more rain, also improve the catch,” he said.

Andhra Pradesh produced 34.5 lakh tonnes of marine and inland fish in 2017-18, the highest in India, according to the handbook of fisheries statistics published in 2018 by the Department of Fisheries, Government of India.

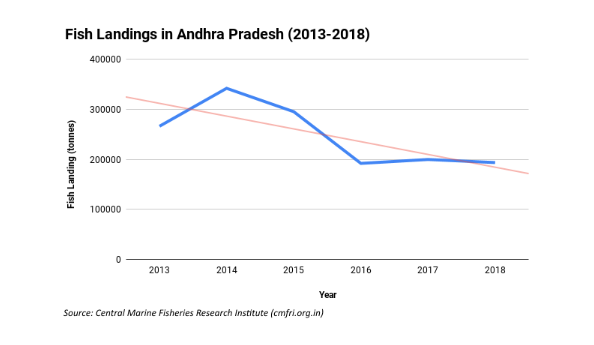

The state recorded a historic high of 3.42 lakh tonnes of marine fish landing in 2014. The figure, however, came down to 1.93 lakh tonnes in 2018 — a 43.6% decrease in the catch, as per the statistics of Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi.

Lack of support

Every year during the breeding season, the fisheries department puts a ban on fishing. Till 2014, the ban was implemented for 45 days; it has now been increased to 61 days — from April 15 to June 14.

“During the ban period, we have to look for daily-wage jobs. July to September is the best season for fishing, while from October to December, not much fish is found,” said Prasad. The fisherfolk are entitled to receive a sum of Rs 4,000 as compensation for losses during the ban period, but the payments are always delayed. In July 2019, the YSR Congress Party announced a hike in the compensation to Rs 10,000 and the fisherfolk are waiting for the decision to be implemented.

Besides the delayed compensation, the community is also struggling with the diesel subsidy for their boats. “The price of diesel is Rs 72 for a litre with a subsidy of Rs 6.03 per litre, an amount fixed when the diesel used to cost Rs 36 a litre,” said P Lakshman, owner of a boat at the nearby tuna fishing harbour.

“For five years now, I have not received any subsidy as the payments are always delayed. I am still hoping the government will increase the subsidy amount to Rs 9 per litre as was announced by Jagan Mohan Reddy, the chief minister of Andhra Pradesh,” he said.

Women find a way

The role of women in the fisheries sector has been critical but often neglected. There were about 1.63 lakh fisher families in Andhra Pradesh with 48.5% women, according to the 2010 census of the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi. Also, about 75% of women were involved in fishing’s allied activities like processing and marketing, the survey showed.

The dwindling fishing catch and the threat of poverty have prompted women to learn new skills to earn a livelihood. They have formed self-help groups to support themselves and their families.

“Self-help groups or SHGs are small groups formed for the purpose of promoting the habit of savings and internal credit among households in rural areas. If we are able to expand their activities, these groups have the potential to act as well-set institutions to serve the credit needs of rural communities and save them from loan sharks,” explained Dr R Ramasubramanian.

These SHGs have saved villages like Anjali Devi’s Kobbarichettu peta, located at the boundary of the Coringa wildlife sanctuary, from economic hardship. That is a big change from the situation not so long ago.

When microfinance companies (MFCs) cropped up in the later part of 2000s offering financial help to rural areas, villagers saw a ray of hope amid the fall in earnings from fishing. Such MFCs had come up all over Andhra Pradesh. But soon, in 2010, the state was grappling itself with a series of suicides of those who had taken the loans. Villagers alleged the suicides were caused by the coercive loan recovery tactics of the MFCs. The government then banned microfinance in the state.

The SHG in Kobbarichettu peta was a result of the outreach programme of the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation. The foundation initially started with an initiative to create awareness about the importance of mangroves for the coastal region.

“With frequent awareness drives by MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, the women were briefed about the importance of mangroves, a resource available to them at a stone’s throw away. They started using it as fuel when they were struggling to make ends meet,” said N Veerbhadra Rao, a development associate with the foundation.

The foundation initiated a mangrove plantation drive in the Krishna and Godavari wetlands in 1996 with the involvement of the local community, who had realised the importance of the ecosystem during the 1996 cyclone. Till date, nearly 900 hectares of mangrove forest area has been restored in these two deltas.

The local community played a major role in activities like mangrove planting, canal digging, etc. Participatory rural appraisal and micro plans were prepared for implementation. Village-level institutions, with equal representation of men and women, were formed to implement the activities.

The awareness drive was soon followed by the formation of self-help groups. The women were then provided micro-credit loans to set up small businesses.

“Friends of our organisation from different countries provided interest-free loans to the rural community living in the project villages,” said Dr Ramasubramanian. “We assessed the needs of the people and forwarded the details to our head office for the loan, after which interest-free loans were released to the women SHGs. Initially, in 2003, an amount of Rs 3,000 was given to eight groups each, which increased to Rs 10,000 each to more than 25 groups in 2010.”

The loans were provided without much paperwork and all the formalities were done by the staff without any cost involved. The women members had the flexibility of repaying the loan in monthly installments. The defaulters, if any, were allowed to pay in the next installments without any penalty. “To make it easy for them, we did not insist that they have to be present during repayment. They can hand over the money to their group or village leader and can go for other work,” said Dr Ramasubramanian.

The socio-economic condition of the fisherfolk in Kobbarichettu peta may have shown some improvement, but the fact is they are still highly dependent on fishing for sustenance.

(Reporting for this story was supported by the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation and Internews)