Burdened by rising diesel prices and increasing irrigation cost, paddy farmers reduce their acreage

Diesel prices have shot up across the country. Paddy farmers complain they are bearing the brunt of the hike as both their input and irrigation costs have increased manifold. They say the recent rise in the MSP of paddy is woefully inadequate by comparison.

Anil Varma is unhappy and worried. He has decided he will cultivate only four to five acres of 13-acre land and leave the rest of it bare.

Standing on the edge of his fields, the 35-year-old farmer said, “I am doing this because the price of diesel has shot up so much,” he told Gaon Connection. Fertilisers and labour costs have also gone up, he added. “When a farmer has to buy the seeds, he pays up to two hundred and fifty rupees per kilo for it. But when it is his turn to sell, he gets no more than ten rupees a kilo,” said the dejected farmer as he surveyed his land in his village Taandi, in Suratganj block of Barabanki district, Uttar Pradesh.

To make matters worse, his entire crop of mentha (fenugreek) that he had planted in four acres of land, was almost entirely destroyed by unseasonal rains in June, he said.

There has been a sharp rise in the price of diesel. On July 1, 2020 diesel in Lucknow was Rs 63.93 a litre. Today (July 6), it costs Rs 89.75 per litre, a hike of more than Rs 25 per litre. Farmers use diesel for their pump sets to extract groundwater for irrigation, and for the use of their tractors and transportation requirements.

The farmers should have been happy as last month on June 9, the central government fixed a minimum support price (MSP) of Rs 1,940 per quintal (1 quintal = 100 kilogrammes) of the kharif paddy, Rs 72 a quintal more than last year when the MSP of paddy was Rs 1,868. The government is on a mission to double the income of farmers by 2022.

Also Read: Grain Drain: Farmers in Uttar Pradesh sell paddy below government rate to repay loans

But farmers are far from elated. “The increase in the MSP is hardly commensurate with other price hikes,” complained Ashish Pandey. “Diesel, seeds, labour… everything is more expensive and the increase in MSP hardly helps,” the 35-year-old farmer from Badrau village in Satna district, Madhya Pradesh, told Gaon Connection.

“Because of the diesel hike, tractor charges have gone up to thousand rupees an hour from five hundred rupees an hour. If we have to meet these expenses, the government should raise the MSP by at least two hundred to four hundred rupees a quintal for it to be of any use to us,” Pandey said.

Cascading effect of increased diesel price

Sukhpal Singh, professor and former chairperson of the Centre for Management in Agriculture, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, said, “Diesel is a widely used commodity. If the price of diesel goes up, the cost of using a tractor to till the land, irrigating it, fertilising it, transporting produce to the mandi… everything goes up,” he explained. “It leads to inflation in the entire system. Every one hikes their prices. It is bound to affect the cost of cultivation” he told Gaon Connection.

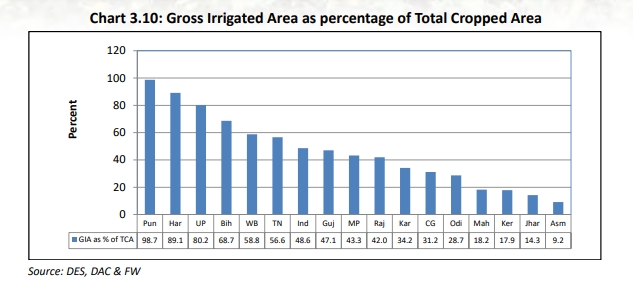

However, according to him, it is not correct to directly link the hike in diesel price to MSP. “In Punjab, where nearly eighty per cent of the irrigation is through electrically operated tubewells, electricity is completely free for the farmers. So, their cultivation costs are not the same as those who do not have free electricity,” Sukhpal Singh added.

While the MSP of paddy has gone up to Rs 1,940 a quintal, many farmers are unable to sell their paddy at MSP. According to a 2016 report brought out by the government’s think tank, NITI Aayog, only about six per cent of the farmers get the MSP for their produce.

Last year, thousands of farmers in Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Bihar, and other states, were forced to sell their paddy at Rs 800-1,200 a quintal in the open market.

Gaon Connection published several reports on how paddy from several states were bought at lower rates from desperate farmers and smuggled to Punjab to be sold at the higher MSP.

Also Read: Rice racket: From the paddy fields of Bihar to the mandis of Punjab

Diesel demand for irrigation

Paddy is the predominant crop of the kharif season. Between June 10 and the first week of August, farmers get busy transplanting the paddy crop. And paddy is cultivated in almost all the states of the country.

Approximately 5.9 million hectares of land is under paddy cultivation in Uttar Pradesh. According to data from the state’s department of agriculture, in 2019-20, paddy was cultivated in approximately 5.9 million hectares. The paddy yield was 17.14 million metric tonnes.

“The biggest expense in cultivating paddy is diesel,” Ankit Singh, a farmer from Hathiya Ghazipur village in Sitapur district, told Gaon Connection.

“I use about six hundred litres of diesel during the crop season (between 110 to 140 days) for my twenty five-acre land. Last year while transplanting, I purchased diesel at sixty five rupees a litre. This year I paid ninety rupees per litre for it,” Ankit Singh said. He also added that while each acre yielded about 15-20 quintals, he could sell the paddy at Rs 1,000 a quintal. “There is hardly any saving in it,” he said. And despite the monsoons, most farmers are dependent on diesel pump sets for irrigation, therefore their expenses go up, he pointed out.

High groundwater dependence

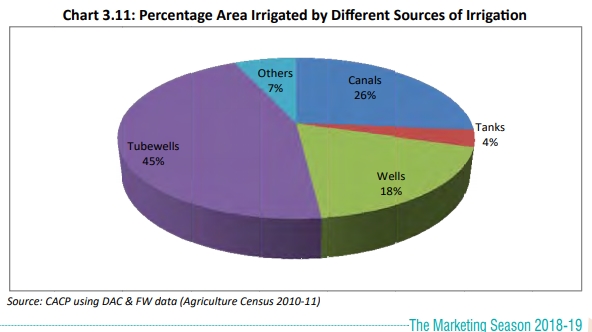

According to the 2018-19 kharif report presented by the Commission for Agricultural Costs & Prices (CACP), 45 per cent of the irrigation is tubewell-dependent in the country.

While the land under cultivation has gone up in the country in the last few years, the dependency on the groundwater for irrigation has also gone up. The water is drawn out with the help of pumps that are run either on diesel or electricity.

Another 2019 report by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, titled Irrigation in India -Status, challenges and options, points out the high dependence on tubewells for irrigation. In 1950-51 dependence on wells and tubewells for irrigation was 29 per cent. This has more than doubled by 2014-15 to 63 per cent. Meanwhile, in the same period, irrigation from canals has decreased from 40 per cent to 24 per cent.

If water from canals or electricity is not available to farmers, they are forced to use diesel run pump sets for irrigation.

Increased targets, dwindling resources

Ramshankar Pandey has more than 14 acres of land in Sungapankh village in Mirzapur, Uttar Pradesh. He uses tractors, pumpsets, etc., in his cultivation.

“When I started farming in the eighties, diesel was three to four rupees a litre. It has skyrocketed since,” Pandey told Gaon Connection. The hike in MSP should keep pace with the hike in diesel price, he added.

The district officials are increasing paddy targets, but farmers are worried about the diesel price. “Last year, 86,256 hectares of land in Mirzapur district was under paddy cultivation. This time the target for paddy is 87,116 hectares in the district,” Pawan Kumar, agriculture officer of the district, told Gaon Connection.

In Sitapur district, nearly 150,000 hectares of land is under paddy cultivation. “Last year, I bought diesel at sixty four rupees a litre. A few days ago, I had to pay eighty seven rupees for it,” Harpreet Singh, from Banehta village in the district, told Gaon Connection. Harpreet Singh has 21 acres of land under paddy. “I use nearly four hundred litres of diesel in the season. This despite using electricity too for more than half my irrigation needs,” he said. “If I was to be dependent entirely on diesel, I would have to sell half my land,” he exclaimed.

Also Read: Why Bihar’s paddy finds welcome in the mandis and rice mills of Telangana

However, government officials claim they are trying to help the farmers. “To help farmers, the government has set up a farm machinery bank in each district. The farmers can hire equipment like tractors, etc., from here at reasonable rates, Arvind Mohan Mishra, deputy director agriculture, Sitapur district, told Gaon Connection. “The rains offer the farmers some respite and the much needed water for irrigating their lands,” he added.

Rise in other inputs costs

“The rate of herbicides has gone up by forty to fifty rupees per litre, in the past one year,” Gyanendra Shukla, who runs a shop dealing with agriculture in Belhara, Barabanki, told Gaon Connection. He said the cost of seeds had also gone up by 15-20 per cent in a year.

“I used to buy nearly twelve kilos of seeds every year. This time I bought only eight kilos,” Jitendra Maurya, a farmer from Piprouli village in Barabanki with 2.5 acres of land, told Gaon Connection. The reason he gave for reducing the acreage of cultivation was, predictably, the rising diesel price. “The diesel costs ninety rupees a litre and the paddy sells for not more than ten rupees a kilo,” he remarked.

“One bigha (5 bighas make an acre) yields not more than five quintals of paddy, which when I sell at thousand rupees a quintal, I get five thousand rupees,” Maurya explained. If a farmer got only that much after all the backbreaking work and investment he made on his farm, a time will come, he will stop farming, Maurya said.

“The farmer enjoys no return from all his hard work and that is the reason many of them are leaving their fields behind and running away to the cities,” Siyaram Yadav, an elderly farmer from Ahara Habibpur Sitapur, told Gaon Connection.

With inputs from Brijendra Dubey (Mirzapur), Virendra Singh (Barabanki) and Mohit Shukla (Sitapur) in Uttar Pradesh; and Sachin Tulsa Tripathi (Satna, Madhya Pradesh)

Read the story in Hindi.