‘Serious’ levels of hunger in India, shows Global Hunger Index; govt terms the methodology ‘unscientific’

Recently released Global Hunger Index report paints a grim picture of the hunger crisis in India. Of 116 countries, India has been ranked 101, which is lower than its rank of 94 last year in 2020. The Indian government has called the report “shocking” and “devoid of ground reality”. Can India achieve ‘zero hunger’ by 2030?

The government data shows less than 10 per cent of children aged 6-23 months in India receive an adequate diet. Photo: Unicef

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) data for 2021 is out. The annual report jointly published by Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe, that tracks hunger at the global levels has ranked India 101 out of the 116 countries. This year, the country has slipped from its rank of 94 last year in 2020.

The country lags behind most of the neighbouring countries, including Pakistan (92), Nepal (76), and Bangladesh (76). Only 15 countries including Afghanistan (103), Nigeria (103), Sierra Leone (106), Yemen (115) and Somalia (116), have fared worse than India.

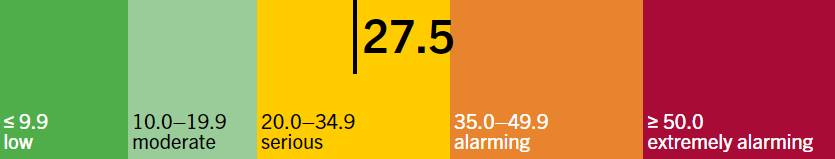

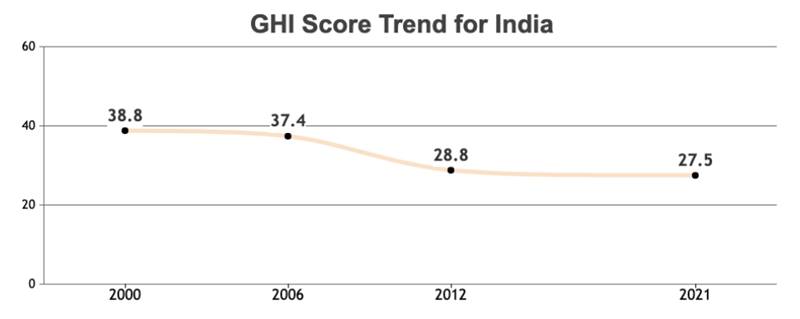

Although India’s GHI score has decreased from 38.8 points in 2000 (considered ‘alarming’) to 27.5 GHI score in 2021, the level of hunger in the country is still termed ‘serious’. The GHI score is calculated each year to assess progress and setbacks in combating hunger. It determines hunger on a 100-point scale, where zero is the best possible score (no hunger) and 100 is the worst.

The poor ranking of India has led to a controversy with the Indian government dismissing the methodology behind the GHI ranking as “unscientific”.

Yesterday, October 15, the Ministry of Women and Child Development said that the Global Hunger Index ranking for India was “shocking” and “devoid of ground reality”.

“It is shocking to find that the Global Hunger Report 2021 has lowered the rank of India on the basis of FAO estimate on proportion of undernourished population, which is found to be devoid of ground reality and facts and suffers from serious methodological issues,” read the official statement of the Ministry of Women and Child Development, stating the methodology used by FAO is “unscientific”.

Indicators for GHI

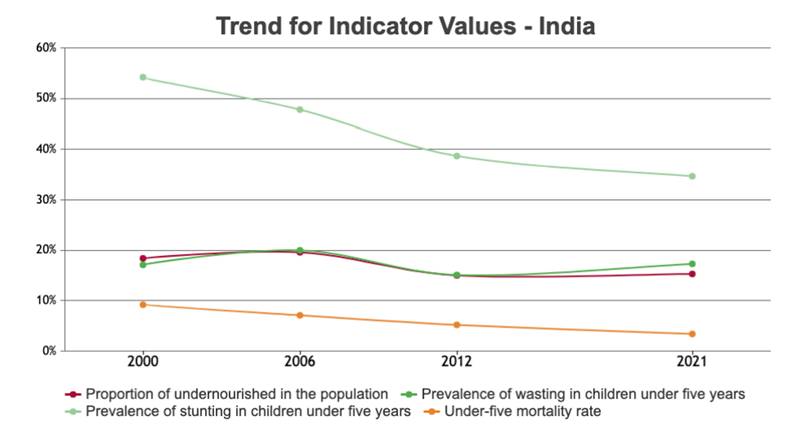

The GHI assessment report is based on the values of the four indicators — undernourishment, child wasting, child stunting and child mortality.

The recently released Global Hunger Index data shows India has the highest child wasting (low weight-for-height) rate of all countries covered in the GHI. At 17.3 per cent, this rate is slightly higher than it was in 1998–1999, when it was 17.1 per cent.

However, the prevalence of stunting (low height for age) has decreased from 54.2 to 34.7 in the past one decade from 2000 to 2021.

Data for GHI scores, child stunting, and child wasting are from 1998–2002 (2000) and 2016–2020 (2021). Data for undernourishment are from 2000–2002 (2000), and 2018–2020 (2021).

Also Read: Rising concern: Rural India faces the double burden of undernutrition and obesity

Meanwhile, the under-five child mortality rate has reduced from 9.2 in 2000 to 3.4 in 2021. Data for child mortality are from 2000 and 2019 (2021).

“It is to be remembered that hunger is one aspect of malnutrition. Large sections of the population may not be hungry but may still not have adequate diets in terms of diversity,” Sylvia Karpagam, public health doctor based in Bengaluru, Karnataka, told Gaon Connection. “People who have a full meal on just rice may not have hunger but they can have several nutritional deficiencies,” she added.

The government’s National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-4 data shows less than 10 per cent of total children in the age group of 6-23 months in India receive an adequate diet.

Further, the 2015-16 data of NFHS shows that 38.4 per cent of under-5 kids were stunted and 35.8 per cent under-5 kids were underweight in India. The NFHS-5 data is yet to be released.

‘Devoid of ground reality’ and ‘unscientific’

The Indian government has dismissed the recent hunger report as based on “unscientific” methodology.

For India’s 2021 GHI score, data on undernourishment values were based on the 2021 edition of the FAO Food Security Indicators.

“They have based their assessment on the results of a ‘four question’ opinion poll, which was conducted telephonically by Gallup. The scientific measurement of undernourishment would require measurement of weight and height,” stated the Ministry of Women and Child Development (WCD).

The public health and nutrition experts say the ministry should rather focus on improving nutrition outcomes of the country.

“There are few issues with GHI 2021 but as far as I know it is not an opinion poll based survey as the WCD ministry has claimed in its statement,” Sameet Panda, member, Right to Food Campaign, Odisha, told Gaon Connection. “Rather than negating the finding calling its methodology faulty, it is essential that we plan well and increase the budgetary allocation so that there is faster improvement in child stunting and wasting in the country,” he added.

“The government should urgently ensure that diet diversity is ensured, adequate and subsidised animal source foods are made available to all communities and all the social security schemes are strengthened,” public health expert Karpagam said. “Eggs should be mandatorily introduced in mid day meal schemes and ICDS [Integrated Child Development Scheme] with fruit or milk as an option for non egg eaters,” she suggested.

Can India end hunger by 2030?

Under the 17 Global Goals for Sustainable Development to improve people’s lives by 2030, Goal 2 – Zero Hunger – pledges to end hunger, improve nutrition, and achieve food security. India has also adopted these Sustainable Development Goals and is committed to them.

But, will India be able to achieve ‘zero hunger’ by 2030? “Obviously not,” said Panda.

“The problem with the nutrition challenge in India is it is not able to reduce stunting and wasting among children. The last NFHS-4 and NFHS-5 have shown we have measurably failed to address wasting. The severe wasting has rather increased,” he said.

The NFHS-4 data shows every fifth under-5 kid in India is wasted and 7.5 per cent of under-5 kids are severely wasted.

A 2019 report by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) highlighted that India reported the most number of deaths — 882,000 — of children below five years in 2018. The report titled ‘State of the World’s Children 2019’, pointed out that malnutrition caused 69 per cent of under-five deaths in India.

COVID19 pandemic and increased hunger

Amid the scenario of under-nutrition and hunger in the country, the COVID19 induced lockdown last year in 2020 enforced to contain the spread of coronavirus disease seems to have made the matters worse.

A Gaon Connection survey conducted in 20 states and three Union Territories last summer, showed that overall around 35 per cent of the households went without eating the whole day either many times or sometimes, and 38 per cent skipped an entire meal in a day several times or sometimes.

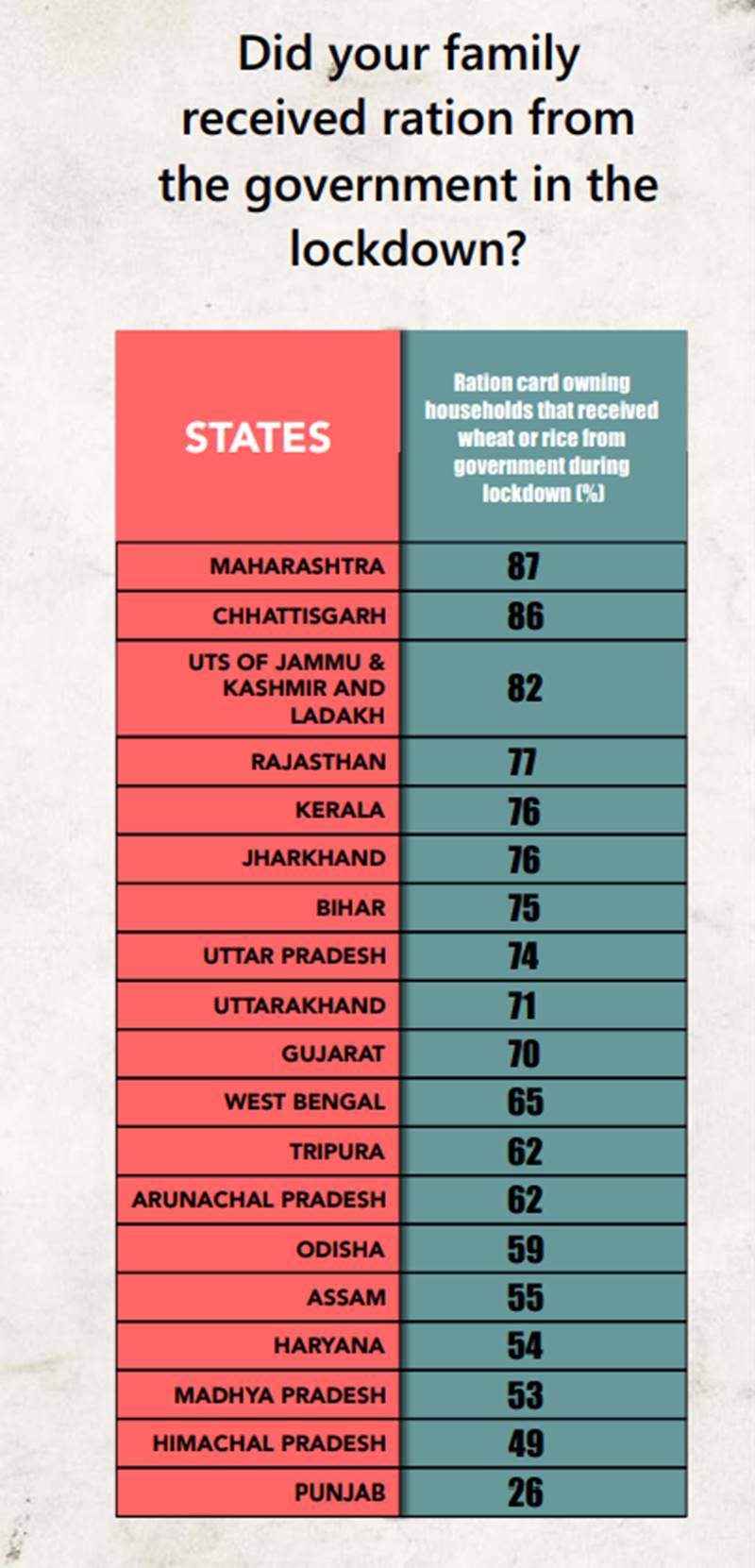

Overall, around nine in every ten households faced some level of difficulty in accessing food during the lockdown. Over two out of three ration card owning households reported receiving ration during the lockdown. A significant proportion (17 per cent) of poor households were found to not have ration cards. Only a little over one fourth of such households reported receiving ration from the government.

The incidence of having gone without food for the whole day was highest in Haryana, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, West Bengal, Gujarat, Jharkhand, and Odisha. The survey also pointed out that Muslim, Christian, and Hindu Dalit households reported experiencing greatest hunger in the COVID19 lockdown.

Also Read: Rising hunger stares rural India in the face as the second wave of COVID invades villages