Monsoon 2020: Large excess season, the silver lining during pandemic, a boost to agriculture and economy

Cyclone Nisarga in June, deficient rainfall in July, record low pressure systems in August, and La Niña in September. This year’s monsoon season draws to an end with a delayed withdrawal of the southwest monsoon.

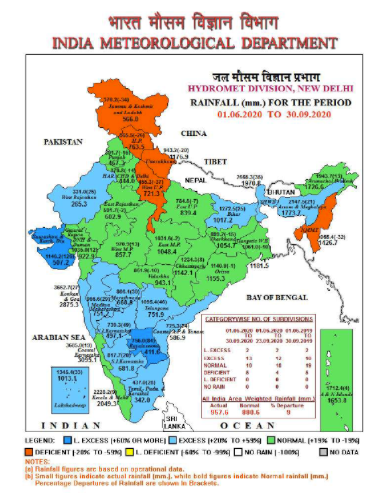

For the people of India, monsoon evokes a lot of emotions – the first monsoon rains bring much needed respite from the scorching pre-monsoon heat and petrichor, the changing landscape with green cover and pristine waterfalls, and above all the fate of agriculture and economy is intricately tied to the performance of the monsoon. A nation of one billion dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic already had too much to handle and a poor monsoon could have been the nail in the coffin for India. But thankfully, the monsoon was benevolent enough to bring much needed cheer to the Indian economy, especially the agricultural hub of India. Infact, it was more than benevolent, ending at a massive 109 per cent of the Long Period Average (LPA), which puts the overall monsoon performance in a large excess category.

This is the first time in more than 50 years that India has seen back to back excess monsoon seasons. Last year’s monsoon had also ended as a ‘large excess’ with 110 per cent of LPA.

However, monsoon 2020 was not short of any drama and it was a rollercoaster season, to say the least. The drama started in the pre-monsoon season (March-April-May) where the monstrous Bay of Bengal hosted the super cyclone Amphan (the first super cyclone in 21 years in the Bay) only to take away most of the ocean energy and leaving it in a somewhat dormant state. Owing to the formation of Amphan, India Meteorological Department’s (IMD) weather forecasting model suggested a delayed arrival of monsoon over Kerala, slated to arrive on June 5, 2020.

Twists and turns in the first half of the monsoon

The first twist in the tale came in the form of cyclone Nisarga in the Arabian Sea, which pulled the monsoon trough along with it, giving a surge to the monsoon currents. The monsoon would mark its on time arrival over Kerala on June 1, 2020 and it came with a bang – the monsoon onset coincided with cyclone Nisarga, a rare cyclone to hit the Maharashtra coast. Making it more rare is the fact that it intensified into a Severe Cyclonic Storm just 24 hours before landfall. Although the monsoon’s arrival caused havoc over coastal Maharashtra, the timely arrival of monsoon during 2020 was an important landmark, given the ongoing economic crisis due to COVID-19. From thereon, there was no looking back and the monsoon currents swept the entire country by June 26, 2020 – a remarkable 12 days before its normal date (i.e. July 8). Thanks to cyclone Nisarga, which pulled the monsoon currents along with it, overall June monsoon performance was satisfactory.

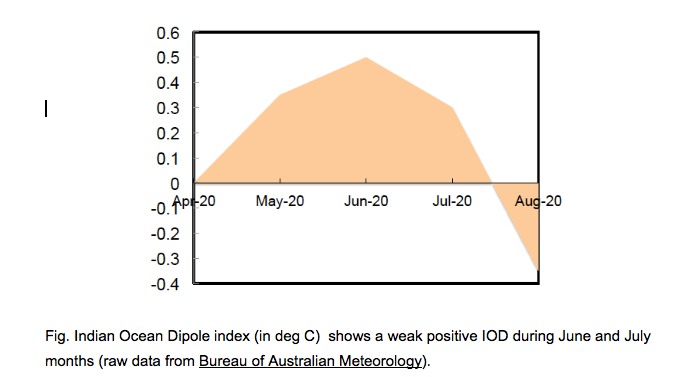

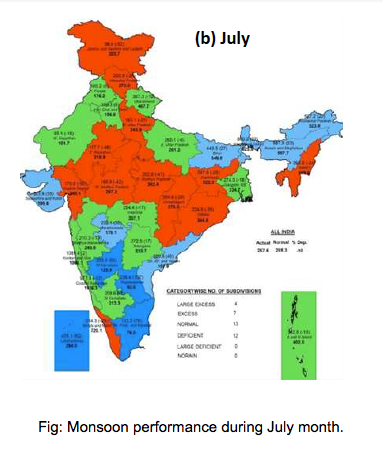

However, a second twist came in July this year. The month of July is very crucial for monsoon, as it is one of the wettest. A standing wave pattern in the West Indian Ocean resulted in a momentary weak positive Indian Ocean Dipole (pIOD) in July that restricted the activation of the Bay of Bengal monsoon branch (pIOD is announced when threshold crosses a value of 0.4, as seen in the figure). As a result of this, the Bay of Bengal had zero low pressure systems in July, which resulted in weak westerlies that did not have the momentum to bring moisture to Central India; evident from the deficit rainfall pattern (shown in red color in the figure) for the month of July. As a result of unfavorable monsoon dynamics, the overall rainfall in July was 9 per cent deficient, raising fear that the monsoon would once again bring misery with a below par performance.

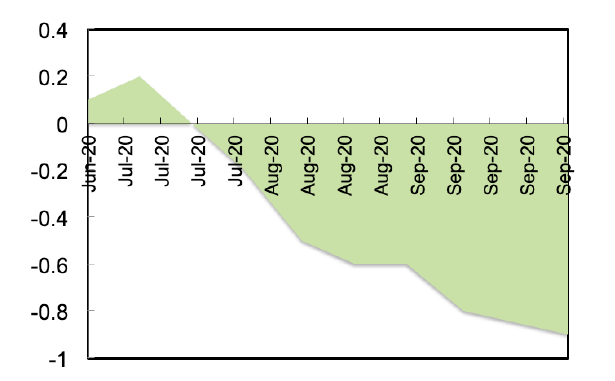

Emergence of La Niña: The hand of God

However, things completely took a turn in August with all global models coming to a consensus that a La Niña is developing in the Pacific Ocean. In short, La Niña is an ocean-atmosphere state where the water pool near the Western Pacific (close to Australia) warms significantly compared to the Central and Eastern Pacific. This manifests in the atmosphere as a strong movement of moisture-laden trade winds from East Pacific to West Pacific and strengthening of the Walker circulation cell. La Niña is known to bring above normal rains to Australia, South East Asia, and India. The more negative the Nino 3.4 index (shown in figure below), the stronger the LaNina, which is officially announced when it crosses a threshold value of -0.8.

The emergence of La Niña in August allowed the westerly winds in the Indian Ocean to strengthen and at the same time allowed low pressure systems to form in the Bay of Bengal – and with that finally the Bay of Bengal had woken up. The Bay would go on to produce a record five low pressure systems in August. The whole of August this year saw 28 active monsoon days as opposed to a climatological normal of 17 days. The July deficit had been wiped out and the performance of August signalled that the year 2020 is indeed going to be a La Niña year.

In the beginning of September, an official announcement came that La Niña has fully developed in the Pacific Ocean, which resulted in normal September rains across India. The performance of monsoon in the second half of the season was the most interesting aspect of Monsoon 2020.

The La Niña conditions further kept the monsoon currents alive delaying the southwest monsoon withdrawal process. As of today, October 9, the withdrawal has not commenced from Central India and West coast of India, signaling a delayed withdrawal from these parts. Looking at the ocean-atmosphere dynamics, back to back low pressure systems in the Bay of Bengal are going to keep the monsoon circulation active and the withdrawal from Central Indian may not happen before October 20, 2020, making it an extended monsoon season.

Lessons learnt from Monsoon 2020

Every monsoon season is different and there is an erudition from each one of them. Last year in 2019, we saw the strongest positive IOD event on record that massively benefitting the monsoon. This year, it was the late emergence of La Niña that saved the monsoon season.

Coming to the monsoon forecast, IMD had rightly accounted for the emergence of La Niña late into the Boreal summer and expected a normal monsoon season (100-105% of LPA) while giving its forecast in April 2020. Private weather agencies like The Weather Channel India gave a similar forecast but was closer to the actual performance, where they predicted that the monsoon would end at 108% of LPA.

So overall, the prediction of monsoon 2020 was a success from all agencies. In my opinion, it is a win-win scenario when the prediction is a bit on the lower side and the actual rain quantum is more. The other way is dangerous, where models predict a bumper monsoon and the actual outcome is a drought.

In conclusion, monsoon 2020 fought the ill effects of COVID19, such as reduced emissions and global cooling due to lockdown, and could be tagged as the real savior of the Indian economy. It probably is the only silver lining of 2020.

Sridhar Balasubramanian is an associate professor of mechanical engineering and an adjunct faculty member at IDP Climate Studies at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (IITB).